Faces Behind D8 - Brian Crowley, Curator - Kilmainham Gaol Museum

Few places in Ireland hold as much history, emotion, and symbolism as Kilmainham Gaol, a site that has witnessed some of the most defining moments in the nation’s story. Behind its thick stone walls and powerful atmosphere is Brian Crowley, the museum’s long-time curator, whose passion for storytelling, empathy for the people behind the past, and deep understanding of Irish history have helped shape how generations of visitors experience this remarkable place.

In this conversation, Brian reflects on his journey from seasonal guide to curator, the challenges of caring for objects that carry both national and personal memory, and why he believes museums are as much about people as they are about artefacts. We talk about the humanity at the heart of Kilmainham, the importance of community in Dublin 8, and what it really means to care for a place so steeped in history.

You studied English and History at Trinity before going on to do a Masters in Museology. What first drew you to working with museums and collections, and how did that path lead you to Kilmainham Gaol?

Well, it actually happened the other way around for me. My first job in a museum, in fact, my first job after graduating, was here in Kilmainham Gaol. I started as a guide for a summer season, then went off to live in Spain for a while. It was around that time I began to think seriously about what I wanted to do with my life.

I’d always loved history, but what really struck me about working in Kilmainham was the experience of sharing history with people, using museums as a way to communicate and connect, rather than just studying in isolation. I realised I didn’t want to spend my life alone in a library! So I came back, did a few more seasons here, and that gave me the experience to apply for a Masters in Museology.

So really, it was Kilmainham that set me on the path to working in museums, and here I am, all these years later, back where it all started. I first worked here in 1996, the year the “new” museum opened. I still call it that, even though we now have guides working here who weren’t even born then, which makes me feel very old indeed!

Kilmainham Gaol is such a powerful place in Irish history. What’s it like to work every day in a space so charged with memory and what does your role involve on a day to day basis?

Yeah, I think people are always fascinated by the fact that I work in the Gaol, that this is where I go to work every day. During the lockdown, that interest got even stronger because I live within the two-kilometre radius, and the OPW wanted a few people to be here. I didn’t want to stay at home anyway, so myself and one colleague were here for most of the lockdown.

People often ask if it feels creepy, or if the sadness of the place ever gets me down. It definitely has a very strong atmosphere, but at this point in its history, I think there’s a real calmness to it. You feel that it’s a place where momentous things happened, but now it’s almost a building at rest. My favourite time here is in the evening, especially over in the West Wing when the sun goes down. It can be very peaceful and oddly beautiful.

In many ways, I think all the trauma and horror of its past are behind it now, and it’s become a reflective space.

In terms of my day-to-day, it’s really varied. Some days it’s very ordinary museum work, cataloguing, answering queries, planning exhibitions, doing research, and other days it’s completely different. What I’m doing today will be very different to what I was doing last Friday. There’s a rhythm to the year too: really busy periods around exhibitions, and quieter times where you catch up on things.

There’s also a lot of contact with the public, which I really like. Because the collection deals mostly with the 19th and 20th centuries, there are still many people with personal or family connections to the place, and a big part of the job is talking to them and helping them find what they’re looking for.

Last week we had an exhibition opening, and I was also doing walking tours of Dublin’s prisons, so there’s great variety. I also look after the collection for the Pearse Museum and the exhibitions there, and I do some work for Derrynane House down in Kerry. So it keeps things interesting!

Is there a particular object, letter, or story in the collection that always resonates with you?

I think my favourite museum object ever might be some shells that belonged to Barbara MacDonagh, the daughter of Thomas and Muriel MacDonagh.

The year after the 1916 Rising, following Thomas’s execution, a house was rented in Skerries for the families of the executed men so they could have a holiday. Muriel was there with her sister, Grace Plunkett, and the MacDonaghs’ two children, Barbara and Donagh. Donagh was in hospital at the time, I think he’d broken his leg.

Muriel was on the beach with Barbara, playing, and she gave Barbara some shells to play with before going into the sea. The story goes that she wanted to swim out to Shenick Island, just off the coast of Skerries, and raise a tricolour there as an act of defiance. But as she swam out, she seemed to have gotten into difficulties or become exhausted, and she drowned.

Grace and the others were on the beach and could see this happening, so Grace was witnessing the death of her sister just a year after losing her husband and brother-in-law. Barbara was scooped up along with the shells, and she kept those shells for the rest of her life. They’re now on display here in the Last Words exhibition.

What I love about them, and why they resonate with me, is that they’re such ordinary objects that became deeply precious. You could go to Skerries today and pick up a handful of shells just like them, but it’s the story behind these ones that makes them special.

It’s not the grand narrative of the 1916 Rising, it’s the story of a little girl who became an orphan, and of the human cost behind those big historical events. I often think about that: we talk about what 1916 means to us, but for someone like Barbara, what did it mean? It meant that within a year, she’d lost both her parents and the loving family she knew had been completely blown apart.

There’s also another object, which again is really quite ordinary.

After the Rising, there was a government compensation scheme, so if you had lost property or had been financially affected, you could make a claim. This particular claim was actually found in a skip somewhere on a street in Dublin and given to the museum years and years ago. It’s by a woman called Sarah Caffrey, who was a charwoman or cleaning lady. She was making a claim, and it’s a very bureaucratic form, you have to state the basis of your claim.

She was claiming for lost earnings because she was wounded on the Tuesday of Easter Week. She was from Corporation Buildings, and she was standing outside her flat there when she was shot in the hand, which meant that she couldn’t work afterwards. There’s information about the people she worked for, she was working all over the city. The one I remember now is a woman on Prussia Street that she worked for.

But then, over the course of the form, she goes on to describe how not only was she shot in the hand, but actually she was holding her daughter, Christina Caffrey, at the time, and her daughter was killed. I remember the first time I was reading this document, you’re thinking, okay, she was shot in the hand, and then you suddenly realise the full tragedy of what happened. It just becomes manifest in that moment.

We have it on display at the moment, and I think it’s a really important reminder to people that the 1916 Rising is both this big national event and also, for many people, particularly the poor of Dublin who had nowhere else to go, it was something that brought real suffering. No one consulted them about whether they wanted their homes and their neighbourhoods to be turned into a battlefield.

I think it’s really interesting the way those people were, in so many ways, disregarded. The British forces were incredibly irresponsible and careless, they saw a military objective, and civilians were just seen as casualties along the way. But you could also ask, did anyone planning the rebellion think about how it would affect the lives of people living there, people who had nowhere else to go?

It’s important to remember that the largest number of casualties in 1916 weren’t the rebels or the British forces, they were the civilians. And I think it’s really important that we acknowledge that. Not as an act of accusation, but just to say that we need to think more, both then and now, about the consequences of war and conflict for ordinary people.

As the 20th century progresses, you see that the people who suffer the most in war are not the combatants, but the ordinary people. War and conflict are always bad news for the people who are most vulnerable.

When you’re working with the collection, do you feel more like a historian, a storyteller, or a guardian?

I suppose your primary role is as a guardian, because your job is to look after the material. But I think a good historian is also a storyteller and that’s what we’re doing in the Gaol. We’re telling a story, and we’re telling it through objects.

What really interests me is the way we, as people, infuse objects with meaning. We use them to hold memory, to carry emotion, and sometimes even to help us deal with trauma. I think we almost invest these objects with something of ourselves. And certainly, many of the objects in this collection have very traumatic histories. In some ways, they were a way for people to process what they’d been through.

An example I often use is a box that belonged to a woman called May Gibney, who was a prisoner here during the Civil War. She was a member of Cumann na mBan and had been engaged to Dick McKee, who was killed in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday during the War of Independence. In this box she kept mementos of him.

Her daughter, the artist Sally Smith, later described how every so often her mother would spend the day with that box just sitting with it. I think that’s a really powerful metaphor for how many people of that generation dealt with the trauma of those times. Often, they didn’t talk about it, in fact, nearly every descendant who comes here tells us, “They never talked about it.” And I think that’s true. They probably only ever spoke about it with others who had gone through the same experiences.

But even if they didn’t talk about it, they were always remembering. And I think many of the objects in our collection are really about remembering, and maybe also about coping with those memories.

So, in terms of storytelling, what we’re trying to do is draw out those meanings: why does this object survive? Why is it important? What does it tell us about the past that we can’t learn in any other way?

How do you balance the need to preserve delicate artefacts with making them accessible and engaging for the public?

Yeah, there’s always a bit of a push and pull with that. Your primary concern is always what’s safe for the object, that’s the main thing. But at the same time, you have to ask, why are we preserving this in the first place? If we’re keeping it safe but no one ever gets to see or engage with it, then what’s the point?

So we try to find a balance. We’ll put certain objects on display, but we’ll control the lighting so it doesn’t cause damage. Or we’ll display something for a limited period and then rest it. For example, we have an amazing embroidery of the Virgin Mary made by Grace Plunkett. We had it on display in the Permanent exhibition and then when we did our centenary exhibition for the women, the imprisonment of women here during the Civil War, obviously it was like one of the stars of the show. But it's also an object which is very, very delicate.

And actually what had started to happen was there's this very heavy silk cord around the edge of it and that had started pulling on the fabric and the warp in the weft were kind of separating out. Our textile conservator said, “You can display it for a few years, but then it needs to come off and rest.” So that’s what we did. Objects are a bit like ourselves, they can go on show for a while, but then they need time to recover.

We also use digital tools to make things more accessible. For example, in the courthouse we have interactive screens where visitors can flip through scans of autograph books. The originals are too fragile to handle, but now when researchers or family members ask to see entries, we can send them digital copies. We only bring out the originals in special cases, like when descendants visit. Seeing the actual page where their ancestor signed can be a very emotional moment.

It’s the same with the building itself. There’s some incredible graffiti here, but if we brought the public up to see it, it wouldn’t last long. When I first started, many of the cells in the West Wing were open to visitors, but we realised people were damaging the original graffiti. So now, public access to prison cells is confined to the East Wing, where we have cells have no original graffiti they can enter.

It’s always a balance, the same reason we limit the number of visitors inside the Gaol. People don’t realise how delicate it is as a building. They think of places like Castletown House as fragile, but Kilmainham is just as delicate in its own way.

We’ll sometimes bring family members in privately to see particular graffiti, thanks to a detailed survey, we now know where specific people signed their names. But again, if we started opening those spaces to the public, the graffiti simply wouldn’t survive.

Kilmainham Gaol sits right in the heart of Dublin 8 - how does the local area influence the work you do at the museum, and do you see the Gaol as part of the local community as well as a national landmark?

It’s true that we have a national remit and a national history, but Kilmainham Gaol is also shaped by Dublin 8 and, in turn, it has shaped the area around it. Kilmainham looks the way it does partly because of the Gaol, and that local relationship is really important to us.

One thing we’re very conscious of is that, while Kilmainham is hugely popular with visitors and tourists, we don’t want to be seen solely as a tourist attraction. That’s important, of course, but we also want to be a place for Irish people and especially for the local community.

That’s why events like Culture Date with Dublin 8 are so valuable. It’s a chance for people from the area to engage with us in a different way. The same goes for our exhibitions, which don’t require booking, we hope that encourages people to just drop in, have a look around, and see what’s on.

Something I’ve found really interesting since we took over the courthouse is how much more connected we’ve become to the local community. We now have guides at the front door greeting visitors, originally, that was just an operational decision to manage numbers. But it’s had this lovely side effect: the guides now know many of the local people by name. There are people who walk their dogs past every day, and they all stop for a chat. You hear the guides say things like, “Oh, I heard so-and-so was in hospital, but he’s out now.” So just that simple act of being at the door has made us part of the neighbourhood in a very real way.

And that’s important, because a gaol is literally built to be intimidating and to keep people out. So anything that helps open us up to the community is really meaningful.

I’ve also really enjoyed bringing our knowledge out into the wider area, like recently, when I did tours for Open House on the last prisons of Dublin, most of which are in Dublin 8 or over in Dublin 7. It’s a way of connecting the history of Kilmainham to the broader story of the city.

One thing that really struck me during COVID was how strong the local connection actually is. When the tourists stopped coming, and there were no flights, we relied entirely on local visitors, and we were still busy. Even though our capacity was small, demand was high. That was very encouraging, because some sites struggled without tourists.

For me, Kilmainham will only be truly authentic if it remains a place that matters to Irish people. If it ever became something just for tourists, there’d be an emptiness to that. And interestingly, what visitors actually want is authenticity, something real. And that’s what comes from staying rooted in the community.

What role do you think Kilmainham plays in shaping how Ireland understands its own history and identity?

I suppose Kilmainham is a really important reminder that we are a country shaped by revolution, by radicalism, and by challenging authority. That legacy, those radical origins of the State, are significant.

It’s also fascinating how central prison became to the struggle for Irish independence, and how Irish republicanism and nationalism, even in the case of people like Parnell, managed to subvert the very idea of imprisonment. A prison is designed to humiliate and diminish, but they turned it into something else entirely; almost a place of elevation and moral strength.

So I think Kilmainham reminds us that this is a country that was fought for, that people sacrificed a great deal to create. And it’s also a reminder that Ireland was born from challenging the status quo. That’s something worth holding onto, and it should make us more sympathetic toward others who are still fighting for their rights in different parts of the world.

I think you can still see that in the Irish character, there’s a strong sense of fellow feeling for people in colonial or post-colonial situations. And that, I think, is an important part of what Kilmainham represents too.

Curating is often about storytelling. How do you approach telling complex and sometimes difficult stories through exhibitions?

Yeah, we do have to tell really difficult stories, and a lot of our history centres around the Civil War, in particular, something people still have differing opinions on.

For me, the great strength of the story of Kilmainham Gaol, and of our collection, is that it’s about individuals. Our role isn’t to be the arbiter of what’s right or wrong in history, but to tell people’s stories. What we can do really well here is put the humanity back into those stories, to show that behind these big historical events are real people, who in many ways were very similar to us. Focusing on the individuals, and trying to humanise them, is key.

That can be particularly challenging when it comes to the criminal history of the Gaol. Interestingly, political prisoners make up barely one percent of all the people ever held here. The vast vast majority were criminal prisoners, mostly very poor people, often drawn into crime through poverty, or arrested simply for vagrancy or being homeless. Poverty is really the driving force behind most of those stories.

But if you look at our collection, it’s completely flipped. We worked out that we only have two personal objects belonging to ordinary prisoners out of maybe 15,000 to 20,000 items. So it’s the reverse of the actual history. And for those prisoners, all you usually have are the registers, a very reductive archive that just lists their names, their crimes, and maybe a few physical details.

One thing we’ve tried to do is humanise those people too. Since the digitisation of the prison records, especially for women prisoners, we’ve been able to trace individuals through their lives, seeing how they reoffended, where they moved, how their circumstances changed. It’s still a limited archive, but it helps give a shape to their lives and reminds us of their humanity.

As a museum, we’re not historians in the academic sense, our job isn’t to make arguments, it’s to present material and stories. We lay the evidence before people, tell them what we know, and allow them to make their own judgements.

Have there been exhibitions or projects you’ve worked on that felt especially meaningful to you personally?

Yeah, well, I suppose personally one of the things I’m really proud of is our Queer History Tours, because it’s something that was very personally important to me. But also, once we decided to do it, it was amazing how much queer history we were able to uncover, all these stories that had been hidden, and how much it meant to people, especially within the LGBT community, to see those histories acknowledged and told.

It was also about showing that the LGBT community is part of the wider story of Irish history. The challenge, of course, is that these are stories that were suppressed at the time, often considered unspeakable, so the act of recovering them has been personally very meaningful. I remember the first time we ran the tours and raised the rainbow flag at Kilmainham. I thought to myself, if you told me back in 1996, in my early twenties, that this would happen one day, I’d never have believed it. So that was something that really meant a lot.

Another thing I’m very proud of was our programme of exhibitions during the Decade of Centenaries, and the fact that we managed to keep it going despite COVID. I remember opening an exhibition on The Forgotten Ten, those executed in 1921, in an empty building with no visitors. We filmed it, put it on social media, and said, “When we reopen, you can come and see this.” I’m glad we did, because it felt important to mark that moment.

Of those exhibitions, the one that meant the most to me was about the executions in Kilmainham Goal during the Civil War. This is a really difficult and heartbreaking part of the prison’s history. Kilmainham was the location of the first executions of the Civil War on 17 November 1922. The four young men shot here were ordinary, low-ranking soldiers who lived locally around James’s Street. I was really struck at just how local this story was, these men would have known the outside of the building well, one of them worked in the Inchicore railway works and would have passed it every day. One aspect of the exhibition I was particularly proud of was rediscovering the story of the Leixlip Five, five young men from the National Army who deserted in late 1922 and were imprisoned here in Kilmainham. What we hadn’t realised until we began researching this story for our Decade of Centenaries commemoration programme was that two of them were executed here in Kilmainham Gaol on 8 January 1923, while the other three were brought from the Gaol that morning to be shot in Richmond Barracks.

It was the first time we’d really told that story properly in Kilmainham. It wasn’t exactly a secret -you can find it recorded in the newspapers at the time - but much of the story had been forgotten or misremembered. It was really through having access to digitised records online that we were able rediscover this history and tell it in the exhibition. I was so moved to see how deeply meaningful that exhibition was to the descendants of these men, and how important it was for them to see that their was being remembered.

Are there any recent or upcoming exhibitions, acquisitions, or projects at Kilmainham that you’re particularly excited about?

I suppose the thing we’re really excited about at the moment is the exhibition we’ve just opened A Prisoner’s Lens: Secret Photography in Kilmainham Gaol, 1921. From about June to December that year, during the War of Independence but after the Truce, there was a brief period when the regime in the Gaol became a little more relaxed. During that time, the prisoners managed to smuggle in at least two cameras.

We think the main person behind it was a prisoner called Vincie Lawler, and he and others began secretly photographing daily life inside the Gaol. They photographed each other in the yards, playing games, taking Irish classes, working in the kitchen, even staging boxing matches and little scenes that look like something out of a silent movie, with hold-ups and dramatic poses. There are also lovely photos of them sitting in the sun with two dogs that lived with them in the Gaol at the time. Unfortunately, the kitten mentioned in some accounts doesn’t appear in any of the photos we have!

Some of these photographs were donated to Kilmainham Gaol years ago, in the 1960s a man named C.J. Daly donated an autograph book he made as a prisoner which contained photographs he took and signatures of about sixty men who were imprisoned with him in the Gaol. We also had a selection of other photos from 1921, but in 2022 the Lawler family gave us over fifty more, a huge addition to the archive. Then last year another branch of the Lawler family also donated letters Vincie Lawler wrote to his mother, giving her detailed instructions on how to smuggle in film and photographic paper. That discovery finally confirmed what we’d long suspected, that the photos really were taken inside the Gaol. For this exhibition, we’ve combined all those materials and also included remarkable footage from British Pathé showing the prisoners’ release on 8 December 1921. It’s the earliest known film footage of Kilmainham Gaol, and we’re showing it for the first time in the very room above the door where they walked out.

What I love about these images is how human they are. Most of the men are very young, casually dressed, with wild hair and suspenders, they actually look like modern hipsters rather than the stiff, formal figures you often see in old photographs. I think people will be really struck by that immediacy.

We’ve also had some incredible donations recently. Just over there is a box containing two complete Cumann na mBan uniforms that belonged to sisters Lily and Sissy Thewlis from Chapelizod, near the Phoenix Park which were presented to us by their family. Lily was imprisoned here during the Civil War. It’s amazing when people arrive with objects like that, things that have been tucked away in attics for decades.

These are the kinds of donations that completely change how we understand the history of the place. So yes, that’s the big excitement at the moment.

What excites you most about the future of Kilmainham Gaol Museum and its collections?

I suppose what really excites me about the future of Kilmainham Gaol Museum is that we’re constantly discovering new things, even about stories we thought we already knew. For example, on the more tragic side, we always knew that the Leixlip Five had been imprisoned here during the Civil War, but it was only recently, through digitised records, that we discovered two of them were actually executed here.

The digitisation of archives has completely changed how we understand the building and its history. It’s opened up whole new areas of research we’d never have thought to explore before, and it means we’re constantly being surprised by what turns up. I love that, the sense that someone might just arrive in one day with a new object or letter, and suddenly we’ll have to rethink everything we thought we knew.

When I started out, researching the old prison registers was painstaking, you’d have to leaf through them page by page, and tracing a single prisoner through the records could take months, even years. Now, with so much material online, we can make connections that would’ve been impossible before.

My favourite example of that is a medal we have upstairs, a British Army campaign medal from the Fenian raids of the 1860s. It was donated in the 1960s by the Restoration Society, who wanted to highlight the Gaol’s transatlantic connections and appeal to American visitors. We’d displayed it for years, assuming it was simply a link to that story. Then my colleague Aoife noticed there was a name and number on the medal and decided to look it up in the British military records.

It turned out the soldier, a man named Henry Rance, not only served in that campaign but later married an Irish woman, settled in Ireland, and was actually imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol twice in the 1890s. So that medal, which we’d had all along, suddenly became one of only two personal items in our collection that belonged to an ordinary prisoner.

That’s the kind of discovery that would’ve been nearly impossible before digital archives. And it’s what makes this work so exciting.

If you could bring one dream project or exhibition to life, what would it be?

I’d really like to do an exhibition on the queer history of the Gaol, or maybe in particular the big Dublin Castle scandal of 1884. It was part of that battle between the Irish Parliamentary Party and Dublin Castle, when it emerged that a number of senior members of the British administration were engaging in clandestine, same-sex activities. It ended up exposing a whole network of men across the city, across different classes, from Gustavus Cornwall, who was the head of the Post Office in Ireland, down to Jack Saul, a former valet who later became a well-known male prostitute in London.

It’s a big story, but the problem is there isn’t much material culture related to it. So I’d like to do something around that.

Similarly, I’d love to do an exhibition that could tell the story of the imprisonment of ordinary women prisoners in the 19th century. Again, for some of these women the only record of their lives are entries in a prison register. So often the exhibitions I really want to do are about the things we don’t have material for. But yes, those are two that I have in the back of my mind.

And then another thing I’d really like to do, and maybe we will someday, is an exhibition about other prisons in Dublin, the ones that don’t exist anymore, and to look at Kilmainham in that wider context. That one might actually be more realisable, because we already have some material and there are places we could borrow from other institutions. So maybe that’s something we could look at in the future.

Working so closely with stories of imprisonment, struggle, and resilience has that changed how you think about freedom, justice, or community?

Yeah, I think it has changed how I think about those things. Obviously, a lot of people end up in prison for valid reasons, and it’s right that there are consequences when people do wrong. But working on the history of prisons, you start to realise that not everyone who ends up in prison necessarily should have been there.

Prisons are a relatively new idea. They only really emerged at the end of the 18th century. Before that, gaols were just places to hold people while they awaited punishment, which was usually physical, public, and in the worst cases, involved execution. The idea of imprisonment as punishment is quite modern. In the early 19th century, people believed prisons could solve crime and completely reform offenders. But by the mid-19th century, it was clear that wasn’t true, and yet the system continued, because what else could you do?

My big takeaway after over twenty years of working on prison history is that, a lot of the time prison doesn’t work. It often doesn’t reform people, and in some cases it can make things a lot worse. More imprisonment doesn’t mean less crime. We continue to rely on prisons because we really don’t know what else to do. People do need to face consequences if they do wrong, but they also need the chance for rehabilitation and the chance to start again. Society has the power to deprive someone of their freedom, which is such a profound thing to do to someone, but it also has an obligation to care for the people it imprisons.

The truth is, most prisoners, then and now, come from economically deprived backgrounds. Poverty is a huge factor in who is inprisoned. I remember John Lonergan, the former governor of Mountjoy, saying that you could trace most prisoners to a small handful of Dublin postcodes. The same was true in the 19th century. It’s a cycle of poverty and crime that just keeps repeating.

We’ve done several art exhibitions with the Prison Education Service, and it’s amazing to see how education and art can genuinely help people turn their lives around. Another big factor is age: most crime is committed by young men. They’re reckless, they make bad decisions, but often ten or twenty years later, they’re completely different people. So as a society, we need to give people the chance for a fresh start when they’ve served their time, because reintegration is where the real challenge lies.

People often ask why Kilmainham closed as a criminal gaol in 1910. It actually closed as part of a mass shutdown of prisons across the country. In the early 19th century, there was a huge prison-building programme, almost every county had one. But less than fifty years later, they were surplus to requirements. That was partly the long-term effect of the Famine, with the loss and emigration of millions of the poorest people.

You can even see it in the prison numbers: when wars break out, the prison population drops because young men enlist; when wars end, the numbers rise again. Most prisoners are young, and many eventually turn their lives around. So that’s where we need to focus our resources — on rehabilitation and prevention, because simply building more prisons won’t solve anything.

So I suppose my conclusion, after all these years, is that prison doesn’t work, at least, not in the way we like to think it does.

If you could highlight one overlooked story or figure from Kilmainham’s past, who would it be and why?

The big difference between men and women prisoners was what happened to them outside the prison. Once women found themselves in the system, it was almost impossible to get out again, because they were considered “fallen women.” In the 19th century, economic opportunities for women were extremely limited, the main form of employment was domestic service, but if a woman had any association with prison or the criminal world, she was considered to have a bad character and wouldn’t be hired. So once women entered the system, they tended to offend and reoffend simply because there was no other way to survive.

The case that’s freshest in my mind is a woman named Anne Hollywood who was held in Grangegorman Female Penitentiary, which opened in 1836 as the first female-only prison in Britain or Ireland. She served fourteen sentences in a single year, nine months in total, often going in and out within days. Many of these women lived incredibly hard lives. They were usually arrested for loitering or disturbing the peace, which we now understand was often code for prostitution. Interestingly, prostitution itself wasn’t a crime, but under the Dublin Metropolitan Police Act, women could be arrested if they were deemed a “source of disorder.”

That became a particular problem in Dublin because it was such a small city and the police knew everyone. Simply being a woman who was ‘known to the police’ in a public space could put you at risk of arrest. Many of these women also struggled with alcoholism, which was likely a way of coping with their circumstances, and you often see attempted suicides recorded too as that was also considered a crime at the time..

Some of these women served over a hundred prison sentences over the course of ten or fifteen years before simply disappearing from the record. It’s an extraordinary and tragic pattern. What’s fascinating is that all of this happened at the height of the Prison Reform movement, when reformers believed prison could rehabilitate. Some of these women were model prisoners, responsive to gentle treatment, compliant, and yet on the most basic measure, prison failed them completely, because they were the ones most likely to return.

Grangegorman itself became a “model prison” under its governor, Marian Rawlins, who was highly regarded at the time. But this pattern of endless reoffending exposed a deep flaw in the reform movement, it showed that prison couldn’t solve the social problems that led women there in the first place.

It’s a very hidden story, even at the time. These women rarely appeared in newspapers unless they did something dramatic. Most were sent to prison on the recommendation of police, without trial. So their voices and experiences were largely erased. That’s why I think it’s such an important story to tell.

Outside of the Gaol, is there a place in Dublin 8 that inspires or feels special to you?

I suppose if I had to pick one place, it would probably be the South Circular Road. I live just over the canal in Dublin 12, right beside it, and I walk along the South Circular every morning on my way to work. I just find it fascinating, the range of buildings, histories, and stories you encounter as you move from the city centre outwards.

You’ve got what’s now Griffith College, which was once Richmond Bridewell, and then all those incredible old houses along the way. When I moved back to being based in Kilmainham full-time, one of the best parts of that decision was realising how much I loved that walk into work. It’s such an interesting stretch and has a really nice feeling about it.

What’s lovely too is how often, through my work, I’ll come across connections to that same area. For instance, we have the hat of James Foran, who fought in the 1916 Rising, on display here. When his family came in to see it, I looked him up and discovered he’d lived at 4 Dolphin’s Barn Street, and it turned out the barber I go to is right next door to where his house used to be. I love those moments where history suddenly feels so close, it’s literally just around the corner from you.

And then, of course, this whole area is threaded through Ulysses, from Leopold Bloom being born on Clanbrassil Street to Molly Bloom coming from the Dolphin’s Barn–Rialto area. It’s such an interesting part of the city, full of layers of history and life. Even after all these years, I still find the South Circular Road endlessly fascinating, it’s just a really lovely street to walk along.

What do you hope visitors take away when they leave Kilmainham Gaol?

I suppose what I really hope visitors take away is a sense of the human stories behind it all.

When people think about 1916, they often see these figures, the signatories of the Proclamation, as monumental, almost mythic figures from history. But what’s remarkable is that when you follow their stories into Kilmainham, when they’re here facing execution, writing letters to their loved ones, or being remembered by their families later, they become deeply human again. You suddenly see them as fathers, sons, brothers, and husbands, as ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances.

And that, I think, is the real power of this place. It’s a building designed to dehumanise people, but it fails, because our humanity is too strong to be erased. The Gaol is full of human stories, of courage, loss, hope, and love, and I think that’s what makes it so moving.

So if people leave here with anything, I hope it’s an understanding that history isn’t abstract. It’s made up of real people who lived, felt, and struggled, just like we do. In some ways they were completely different from us, but in other ways, they were exactly the same. And I think that’s a beautiful thing to take away from a place like this.

And finally, if you could sum up what being a curator here means to you, how would you put it in a sentence?

I suppose the root of the word curator comes from the idea of care, and that’s really what it means to me. Our role is to care, not just for the objects in the collection, but for the people connected to them: those who donated them, those whose stories they tell, and those who come here to learn about the past.

Even though the objects themselves are inanimate, what they represent is very much alive. So being a curator, for me, is about caring for both things and meaning they contain while also helping others connect with them in a way that lets the history speak for itself.

Quickfire Round

A book you always come back to?

I’ll give you one fiction and one non-fiction. The book that probably made the biggest impact on me in terms of history and culture is Reinventing Ireland by Declan Kiberd. When it came out in the 1990s, his ability to look at Ireland through the lens of postcolonialism and to reclaim figures like Wilde and Joyce within an Irish context really struck me. He deals with big, complicated ideas but in a very readable way, that’s what I love about it.

For fiction, it would have to be Beloved by Toni Morrison. I first read it in university, and it completely changed how I thought about literature, about memory, history, and what writing can do. She’s just the most extraordinary writer.

Your favourite spot in Dublin 8?

I love the Tenters in spring when the cherry blossoms are out, it’s really magical. Oscar Square especially, the houses around there are so lovely. I also think the housing around Mount Brown, heading up towards St James’s, is also gorgeous and I love wandering around up the hill along those old terraces.

A museum or heritage site (outside Kilmainham) you love to visit?

I’m a big fan of 14 Henrietta Street, it’s just beautiful, and what they’ve done there is amazing. Abroad, I love Lisbon, especially the Castelo de São Jorge, with that incredible view over the city. The Gulbenkian Museum there is another favourite; it’s small, perfectly formed, and full of treasures.

And in the UK, I’d say Kelvingrove in Glasgow. It’s one of those grand Victorian museums, full of character, and what I love most is how much the ordinary people of Glasgow love it. It feels like the city’s heart.

A historical figure you’d invite to dinner?

Michael Davitt. He came from such humble beginnings, working in cotton mills in Lancashire, where he lost his arm, and yet went on to become a Fenian, a Land League leader, and later a campaigner for human rights. He even went to Russia to report on the pogroms. He just seems like a fascinating, principled person. A lot of historical figures would be intimidating to meet, but I think he’d be genuinely interesting to talk to.

The last exhibition you went to that really inspired you?

The Jewish Museum in Vienna really stayed with me. They had this brilliant display where offensive caricature figures were turned backwards, with mirrors behind them. It forced you to think about what you were seeing, you became an observer rather than a passive viewer. It was a really smart, sensitive way to deal with difficult material.

Similarly, the Museum of Film and Television in Berlin, beautifully designed. They handle challenging subjects like Nazi propaganda films in such a considered way, presenting them in drawers so you view them critically rather than emotionally. I was so impressed by how much thought went into that.

Best thing about working in Dublin 8?

I love that it’s a city neighbourhood that still feels human in scale. There’s such a strong sense of community, I pass the same people every morning on my walk to work. It’s still a part of the city where people live, and that’s what makes it special.

Favourite pub or café in the neighbourhood?

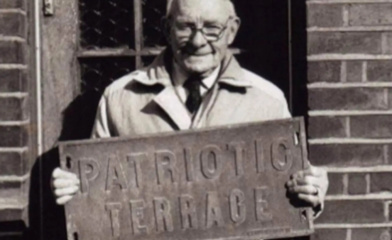

Every morning I stop into The Bakery in Rialto for coffee, thankfully I’m never too hungry first thing in the morning, or I’d be tempted by all their amazing cakes. I also like The Place in the Bird Flanagan for coffee. Now and then myself and my husband head to Noshington’s on the South Circular Road we feel like treating ourselves to breakfast or lunch.As for pubs, The Patriot’s Inn has become a bit of an institution for us at the Gaol, and The Royal Oak is a gem, you feel like you have wandered into a little pub in the Irish countryside.