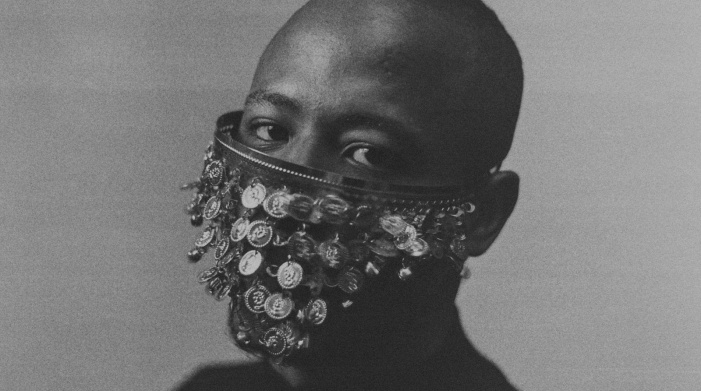

Portrait of Ishmael Claxton by Conor Horgan

D8 Artist Spotlight - Ishmael Claxton

Born in New York and now living in Dublin for over a decade, photographer Ishmael Claxton uses his lens to hold a mirror up to society and spark conversations about identity, culture, and community. His work spans international projects like The Migration Project, a powerful portrait series exploring the lives of migrants across Ireland and Morocco, to deeply local stories such as Capall Gang, which captures the traditions and resilience of Dublin’s horse-owning communities.

Alongside his personal practice, Ishmael is also a co-founder of the ÍOVA Club, a photographer-led collective that supports and amplifies image makers through exhibitions, talks, and community events. With his work exhibited widely in Ireland and internationally, Ishmael continues to use photography as a tool for storytelling, whether tracing global experiences of displacement or documenting the unique spirit of Dublin 8.

In this interview, we speak with Ishmael about his creative journey, the stories behind his projects, and why shining a light on overlooked communities matters now more than ever.

Can you introduce yourself to us - who are you, and what kind of art do you create?

Hello, my name is Ishmael Claxton. I'm originally born and raised in New York City, but I've lived all around America and Europe. I've lived in Ireland for the last 11 years and I am a visual artist, but I use photography as my primary means to create. I currently live in The Liberties in Dublin 8.

What brought you to Ireland, and specifically to Dublin 8, and what does being based here mean to you as an artist?

What first brought me to Ireland was actually quite unexpected. Back when I was in New York, I was running an Airbnb business and rented to two Irish visitors. One of them, Loah, came on her own after her friend couldn’t make the trip, and while she was there, we became really good friends. A couple of years later, Loah introduced me to her friend Violet, who was visiting from Ireland. She thought we’d get along well and she was right, we got on like a house on fire!

At the time, I was already planning to move to Europe, originally with Germany or Italy in mind. I spent some time between Berlin and Paris, but I stayed in contact with Violet. When I was trying to figure out the visa situation, it turned out Ireland was the most straightforward place to study as an American, and I’d always wanted to study art in Europe. So between the practicalities of the visa and the chance to study, I ended up coming here.

Being an artist in Ireland has been really interesting. It’s a smaller scene compared to New York, which I think of as a kind of training ground where you can sharpen your skills, learn the dynamics of the art world, and then bring that experience into bigger spaces. What I love about being in Dublin 8, especially in the Liberties, is that it has a New York energy to it. It reminds me of old Bushwick, where I grew up. There’s a real community feel here, and that extends to the art scene as well. It’s small, almost like a family, sometimes supportive, sometimes competitive, but that intimacy has shaped my journey over the past 11 years.

Where do you draw inspiration from, either within the area or beyond?

A lot of my work is inspired by class, culture, and politics, and that naturally connects to the Liberties because the area has such a strong history in all those things. The Liberties has always had this unique identity, it was never fully touched by the British, and that independent spirit still comes through in the community today. That sense of resilience and togetherness is something I feed into my work.

One of my projects, Migration/Immigration, looks at how people move around the world while holding on to their culture. That’s something I see reflected in the Liberties too. It’s a multicultural place, but at the same time, it has its own cultural nucleus. What’s interesting is how it expands by welcoming and absorbing other cultures while still keeping its identity.

Another project of mine, Capall Gang, is rooted directly in the Liberties. It explores equestrian subcultures and issues of class, which tie back to the local tradition of horse carriages in the area. That history and imagery are a big source of inspiration for me.

I also take inspiration from the physical environment here such as the old Iveagh Trust buildings, the Guinness Storehouse, even places like Rupert Guinness Theatre which I got to explore recently. The mix of history, architecture, and community energy all feed into my practice. Inspiration is everywhere in the Liberties, and I try to soak up as much of it as possible.

Can you share a glimpse into how you approach making your work?

For me, the process always takes time. A lot of it starts in a theoretical space. I’ll begin with an idea, and then I work outwards from there. I ask myself: What do I want to say? What do I want to capture? Where should it happen? How big should the project be?

It’s almost like a formula I’ve developed. I piece those elements together, and the work gradually takes shape. From the starting idea to the final outcome, it’s a progression, and I usually keep going until it feels like I’ve reached a natural endpoint.

Afro Irish Looking Ahead, Ishmael Claxton

Can you tell us a little bit about the Migration/Immigration Project. What did you learn about resilience and identity through the stories of the people you photographed for the Migration/Immigration Project?

I started the Migration/Immigration Project about ten years ago, when I was still in school. The idea really began after my first experiences moving here. I went to the GNIB, and when I told them I was Afro-Latino American, their response was basically, “You’re just American.” That made me stop and reflect on what identity actually means, and how we carry it when we move somewhere new.

I wanted to explore how people adapt to a new place, how they hold on to elements of their own culture while also taking on parts of another, and where that midpoint lies. In the early stages, I photographed people I knew: friends, collaborators, first-generation Irish, or people who had moved here as kids. The focus was always on how they were balancing their cultural roots with their life in Ireland.

Later, during a residency in Morocco, I expanded the project by meeting people on their way into Europe. I started asking the same set of questions everywhere, whether in Morocco or Ireland, and weaving together those stories. What stood out to me was how different the reality was from the stereotypes people often have about migrants or immigrants. There’s this negative perception, but when you sit down and actually listen, you realise most people aren’t here to “take advantage” of anything. They’re here to build new lives and to contribute to the culture they’re joining.

Some stories were particularly powerful. I photographed two men who were a couple, both bankers and highly educated, but they had to leave their country because of their sexuality. Their lives were at risk where they came from, so they came to Europe hoping for safety and a better life. But even then, they ended up facing new challenges here, like Direct Provision or even living in tents. It showed me how resilience often comes from navigating things that are completely out of people’s control.

So for me, the project is about breaking down assumptions and showing that behind every migration story, there are real people who are talented, resourceful, and resilient and who are not just surviving but also adding to the culture of the places they arrive in.

Finding the Rhythm of Intimacy - from Queens Collective Residency, Morocco

How do you balance the intimacy of personal storytelling with the broader global issue of migration in your portraits?

For me, it all comes down to building real relationships. In the first part of the series, many of the people I photographed were already friends or people I knew, so there was a natural closeness. Later, when I was in Morocco for six months, I took the same approach. I didn’t just show up with a camera, I spent time getting to know people first. That way, when I did take their portraits, it wasn’t just about capturing a story and walking away. It was about creating a lasting connection.

A lot of the people I photographed, I’m still in touch with today. For example, two of the young men I met in Tangier were trying to make it into Europe. One eventually got to Spain and we still talk every six months or so. The other made it to Poland, and now he’s studying IT at university. Hearing updates like that means a lot to me; it shows that the work isn’t just about an image, but about following their journey and being part of their story in some way.

That’s what keeps the work intimate. People are willing to open up when they feel you’re present with them, not just for the photo but for the long term. At the same time, those individual stories reflect the bigger global issues of migration and resilience. It’s through the personal that you see the universal.

Rebel, Rebel - Ishmael Claxton

What do you hope audiences take away from seeing these portraits, both about migration and about humanity more broadly?

For me, it’s about challenging people’s preconceptions. We’re constantly bombarded with propaganda and fake news, and migrants are so often painted in a negative light. There’s this idea that they’re lazy, or here to take jobs, or take resources, or even relationships. Those stereotypes come up again and again.

What I want to show is that behind every migrant, there’s a backstory, and that backstory is key to understanding their present situation. Many of the people I’ve met are incredibly community-oriented. They’re trying to hold onto parts of their culture while also becoming part of a new one. That balance is not easy, and I don’t think people always appreciate how hard it is to adapt while staying true to yourself.

At the same time, I think we forget that people are dealing with their own struggles here whether it’s housing issues, unemployment or dependence on the state. And it becomes easy to project frustrations onto migrants, to blame them for problems that already exist. But in reality, many of the people I’ve photographed are working incredibly hard to build new lives and to contribute.

I think it’s important to highlight those journeys. You might meet someone in a refugee camp, and seven years later they’re studying at university or doing something positive in their community. That kind of resilience is powerful. And yet, I also know people who’ve been standing on the same street corner for seven years, doing nothing, and still blaming immigrants for their situation.

So what I want people to take away is that migrants aren’t here to take, rather it’s that they’re often giving back, and giving a lot. If you take the time to listen and to see the longer timeline of someone’s journey, you realise just how much determination, resilience, and humanity there really is and a willingness to make a better world.

The Boys IV part of the Capall Gang Series

What inspired you to create the Capall Gang series, and how did you first connect with the horse-owning community in Dublin?

The Capall Gang series really grew out of a mix of things. Part of it goes back to my daughter, Nancy Bell, she’s a big “horsey” girl. When I first moved here, about ten years ago, we started going to Ballinasloe Fair. It struck me right away as this really unique place where different worlds collided, you’d see indigenous travellers, settled people, and even more “posh” Irish folks all coming together around horses. And that fascinated me, because so much of my work looks at class. Horses became this unexpected crossover point, where groups of people who might usually be seen as separate, or even judged, were finding common ground.

From there, the interest just deepened. I went back to Ballinasloe year after year, and later I got an Agility Award, which allowed me to travel to different horse events around the country. I went to everything from the Galway Races to Laytown races, carriage driving and even some hunts. It was this whole spectrum, from the very elite to the very grassroots.

And then, living in the Liberties, I naturally got to know some of the lads who kept horses. During lockdown, they actually asked me if I wanted to come out with them when they’d take the horses around the city. So I started going every week, just tagging along. That’s when the project really took on an intimate side, because I wasn’t just showing up with a camera, I was building relationships. They welcomed me in, and I realised how different the reality of who they were was compared to the stereotypes people might hold. They were just so warm, and to this day if I see them riding past, they’ll shout out my name to say hello.

For me, the horses themselves also carry a lot of meaning. They’re deeply tied to the land, to tradition, and to survival, even as the world around us becomes more industrialised and automated. And they cut across every class line, from a horse worth half a million at a race, to a horse pulling a carriage through the Liberties for €50. Horses become this lens to unpack so many layers from class, culture, community, history, even environmental change. And that’s really what the Capall Gang project is about - exploring that intersection.

Jockey An Súl part of the Capall Gang Series

Is there a particular story or person from the horse-owning community in the Liberties that really stands out to you?

They’re all great lads, honestly. I kind of think of them like modern-day gladiators, they’ve got this reputation that makes people wary, but once you actually spend time with them, you realise they’re gentle, warm, and just trying to live their lives.

Like, there’s one young lad, mixed Afro-Irish, everyone calls him Snoopy. Lovely guy. He met my uncle when he was over visiting from New York, and even though everyone in that world usually goes by nicknames or street names, he introduced himself with his real name. Very polite, shook his hand, said “nice to meet you.” My uncle came back to me afterwards like, “your friends are really nice.” And that respect goes both ways. They’ve always treated me really well.

You can see it especially in how they treat their horses. The bond is strong, it’s like family. To them, the horse isn’t just an animal, it’s almost like a child or sibling. And that connection is really beautiful to witness.

Sometimes people ask me, “are those lads actually taking care of the horses?” And I tell them straight, they take better care of their horses than plenty of people I’ve met who have eight or nine of them! There’s a real stigma around them, but if you scratch beneath the surface, you see they’re just ordinary people, very sweet and full of kindness, and very serious about what they do.

I’ve even been to a couple of little parties at the stables, nothing wild, just chilled-out vibes, like hanging with any group of friends. That’s what’s stayed with me most, the normality of it, and the gap between who people think they are, and who they actually are.

What role do you see photography playing in preserving or amplifying these kinds of community traditions?

Photography has always carried a lot of roles. One of the earliest was pure documentation, capturing a place, an object, or a moment so that others could see it. If you look back at the early 1900s, people were photographing places like Egypt or the Sphinx, or the streets of Paris. These images made faraway places feel exotic, desirable, even if you’d never set foot there.

At the same time, photography was also a thing of status and leisure. Only certain people could afford portraits, and when they did, they’d put on their best clothes, stand in front of their land or their house, and show their wealth. It was a way of saying: this is who I am, this is what I own.

Moving into the modern era, it also became a tool for documenting history in a much more immediate way. There’s a famous French photographer Eugène Atget who captured Paris Just before the bombings of World War I and now those images are invaluable historical records. And the same is true today. Even in the show I’m in right now,”I LIVE HERE” there’s a photo of flats in Dublin that are boarded up. They could be demolished any day, but the photo preserves them. That’s a piece of history. Another shot of a ruined house - same thing. These images become time capsules.

Photography also works on a deeply personal level, like when you see an old photo of your mother or your grandparents, maybe when they were your age. It’s like a time machine. You connect across generations in an instant.

That’s why I think photography is so powerful for community traditions. It preserves not just the faces, but the atmosphere, the spirit of a place. In the Liberties, for example, you’ve got local photographers like Francis Brown. Who documented shops and street life up til 1960. Seeing those images now, alongside the present-day reality, you really feel the change.

Even in broader history, the same applies in the historical centre of Dublin, you can watch old footage of Kennedy visiting Dublin near where the Spire is now but before it existed. Again, the photograph or the film places you right there.

And when you think about it, the transition from black-and-white to colour wasn’t that long ago only in the 1900s. In terms of human history, that’s the blink of an eye. And yet, that shift completely transformed how we see ourselves and our world.

So for me, photography will always carry this role: as documentation, as memory, as proof, and as a way of connecting past, present, and future, whether in the Liberties or anywhere else.

Is there a place in Dublin 8 that sparks your creativity or holds special meaning?

Yeah, like I was saying before, I’m really big on architecture. I love spaces like Tailor’s Hall. I did a group show there this year and just loved it. The building, the history, the atmosphere, it’s inspiring.

But for me, it’s not just architecture, it’s also the community. When I was working on one of my projects, I spent time with local business owners, and some of them had been there for four or five generations. It really blew me away to see small businesses still going, carrying that family tradition. That sense of continuity really inspires me.

And then there’s the cultural side and the mix of heritage and everyday life. Like, I love jazz, and there’s always pizza jazz nights at Lucky’s. My good friend Daragh plays keys there, and it’s just such a good vibe.

I also work out of La Cathedral Studios, and it’s a great group of artists there, there’s a really creative energy about the place. And of course, I love the cathedrals themselves. John’s Lane Church, with those Harry Clarke stained glass windows always inspires me. Even the Rupert Guinness Theatre, I was in there the other day, and it’s such an interesting piece of architecture.

That’s the beauty of the Liberties. It’s big, it stretches across different little pockets, and each has something unique. And since I both live and work here, I feel fully rooted in it. It’s home and inspiration at the same time.

Untitled I, Natural History Museum, Dublin, 2025 Specimmen shown: NMINH: 1902.281.1 Indian Elephant Elephas Maximus (Linnaeus, 1758)

What’s something you’ve been working on lately that you’re excited about?

There’s been a lot going on these past few months, so it’s hard to pick just one thing, but I’ll run through a few highlights.

I did a project at the National Concert Hall where I created visuals to go along with a small symphony. It told the story of people of colour in classical music. I worked with original notes, researched the history of the composers and the times they lived in, and then built a visual story to sit alongside the live performance. I think I made about 20 of those, and I also showed some physical pieces outside of the concert.

On top of that, I had a residency at the Photo Museum, which had two parts. One was showing my Migration/Immigration Project, and the other explored decolonising museum collections. I worked with the Natural History Museum, use of a special blue-tinted filmstock references the Irish term for a black person “duine gorma”, it was about looking at collections from a different perspective.

Right now, I’m also preparing a solo show at the United Arts Club. I did a residency at the Santa Fe Photo Center in the U.S., working on a project that connects back to Capall Gang.

This year I’ve also shown work internationally, in Arles, in Italy, and next month I’ll have a piece in a show at the Glasgow Photo Museum.

So yeah, it’s been a busy stretch, but an exciting one.

What’s next for you as an artist?

Loads. Honestly, this is just the beginning.

Like I was saying earlier, I see Ireland as a kind of training ground. I love it here, but because it’s a small place, you can really sharpen your skills, build projects, and then take that experience into bigger arenas. That’s where I’m at now, using what I’ve learned here to push further.

Right now, I’m working on some projects in New York and looking at ways to build connections between there and Ireland. One of the big ones coming up is a project linking New York and Dublin which I’m really excited about, so look out.

But yeah, it feels like things are only just getting started.

Jabu The Black Cowboy in The Liberties

Quickfire Round:

What three words describe your art?

Revolutionary, Thought-provoking, Synergy

Favourite time of day to create?

All the time

Coffee or tea while working?

A coconut iced latte with a sprinkle of lion's mane mushroom for memory boosting

A Dublin 8 landmark you’d put in a picture?

I’d probably say the Iveagh Trust buildings, I really love those. Either that, or the horse stables near Francis Street. Actually, Francis Street itself would be a good one, with all the antique shops. Yeah, that’s definitely a favourite spot of mine.

One local artist/creative you admire?

My friend, Paul Duane, he’s a film director and also lives in The Liberties. And PeachsInk - who is the owner of her own Studio EX on Francis Street.

Where can people find or experience your work?

https://ishmaelclaxton.com

@ishmaelclaxtonphotos