Faces Behind D8: Bren Berry - Vicar Street (Aiken Promotions)

For more than two decades, Bren Berry has been a quiet constant at the heart of Dublin’s live music and cultural life. As a long-time programmer at Vicar Street, he has helped shape one of Ireland’s most loved venues into a space defined not just by world-class performances, but by care, community, and deep relationships with Irish artists.

But Bren’s connection to Dublin 8 runs much deeper than his working life. With family roots in The Liberties, including the Iveagh Trust buildings where his mother grew up, the area has been part of his story since childhood. Long before Vicar Street opened its doors, Bren was absorbing music through family gatherings, Radio Luxembourg, trips to the Dandelion Market, and formative years spent between Dublin and Brixton.

A musician himself, Bren first came to prominence as a member of Revelino, before stepping behind the scenes and eventually finding a new creative voice later in life as a solo artist. His debut album In Our Hope Stars Align weaves together love letters and protest songs, reflecting both personal experience and a lifelong engagement with culture, place, and politics.

In this conversation for Faces Behind D8, Bren reflects on growing up around The Liberties, the evolving spirit of Dublin 8, the responsibility of stewarding a cultural space, and the unexpected joy of rediscovering his own voice as a songwriter.

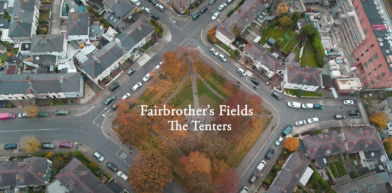

Bren Berry in The Thomas House

You’ve had such an interesting journey from spending lots of time in The Liberties when you were growing up, to playing in Revelino, to programming one of Ireland’s most famous venues. Can you tell us a bit about your background and how music first became part of your life?

I was born in 1963 and lived on South Dock Street in Ringsend between ’63 and ’68, where my father was from. My mother was from the Iveagh Buildings, and I spent a lot of weekends there with my Aunt Norrie and my grandparents, from the time I was born right into my teens. I used to wander up to the Dandelion Market to buy second-hand comics and then I started buying records - I saw U2 there in 1979 for 50p.

From 1970 to ’79, I spent every Christmas in Brixton with my Aunt Norrie. That was an amazing part of my upbringing too, being in Brixton throughout the ’70s, and it had a very formative impact on me. My aunt was an Elvis Presley fanatic and always had the radio on – she hooked me up with Radio Luxembourg. I used to watch Top of The Pops with my mother and my first real love musically was glam rock, bands like Slade and Sweet.

When I left school in 1981, I worked in Irish Life until 1984. I made great friends there who are still friends, but it was soul-destroying work for me. I decided I wanted to be a social worker so I gave up a very secure job and went back to college for four years to study social policy.

I bought my first guitar when I was 20 and then, in the middle of college in 1986, I joined a band, another left turn! The day I finished my final exam, the three other lads in the band gave up their jobs and we were basically on the dole from June 1988 until July 1998, when I started working for Aiken Promotions in Vicar Street.

In the early 90’s, when we were called The Coletranes, we had a record deal in America that came to nothing. In 1993, we called their bluff and I became our manager. We transitioned into Revelino, changed some band members, and reinvented ourselves as a fully independent band. I took control of the management. We decided that if we wanted to make music, we would have to do it ourselves. So, we did.

We worked hard and funded our debut eponymous album ourselves and were about to self-release it but at the last minute we teamed up with Shane O’Neill from Blue In Heaven and his brother Brian who were in the process of setting up Dirt Records. Their father Seamus ran Gael Linn and they felt like perfect collaborators for us. Dirt was an amazing Irish independent label with lots of great bands including Sack and The Idiots. We released a second album on Dirt in 1996 called Broadcaster and then around 1997 it felt like the wheels were starting to come off. I started doing part time work including working in Bruxelles.

I played football with Peter Aiken then and he called me in July 1998 and asked me to meet him in Vicar Street. I assumed he wanted the band to do a gig, but instead he put a job description in front of me and asked if I would come and work for Aiken Promotions and help him to establish the venue. I met the band in the studio in Space 28 in North Lotts where we were working on our final album, and they thought it was a great opportunity that I should jump at. So I did and I grabbed it with both hands and here I am 27 years later.

We released our final Revelino album “To The End” in 2001 and did a handful of shows. It’s probably our best record, but we had lost most of our audience. Five years had passed since the second album and people had moved on. It was over and we just kind of faded away rather than ever officially calling it a day.

I hung up my guitars and never missed playing music, not for a second. I never stood on the Vicar St stage thinking I wished I was up there playing. Then during lockdown in 2020, we re-released our debut album from ’94 on vinyl for the first time and it went to number one in the indie charts, which was very gratifying, especially during such a bleak time. We had a drunken Zoom meeting every Friday night with three of us from the band (me and the Tallon brothers), our sound man Ro McHugh, our old manager Dave McMorrow, and Barry Woodley who played bass with us very early on when we were briefly called The Crocodile Tears. Barry kept giving out to us because none of our music was online and he offered to build us a Revelino website. That led me to reach out to Hugh Scully & Donagh Molloy at Dublin Vinyl, who were brilliant, and we re-released the debut album on vinyl for the first time in Oct 2020. To our surprise it really struck a chord with people and went to number one in the Irish Independent Charts which felt like a really beautiful full-circle moment.

That nudged me back into picking up the guitar again and then I did a very basic creative writing course which definitely helped me to finally crack the songwriting code which was always an elusive mystery to me. I had lots of musical scraps which I had never played to anyone and then in May 2021, I played some of them for my friend Ciaran Tallon. He liked them and encouraged me to try to finish one song and then on Bob Dylan’s 80th birthday, I finally wrote my first complete song. I thought that rather than murdering one of Bob Dylan’s songs, I would celebrate it differently, by trying to become a songwriter in honour of Bob's 80th.

I could never find my own singing voice before that either. I felt that I could sing, but not my own songs with my own authentic voice. That day in the shed, something told me to drop the register of my voice, and suddenly I found it, in every sense. It was an epiphany. The door just flew off the hinges. I found my voice in every sense of the word, not just my singing voice.

How did your early experiences as a musician shape your understanding of live performance and audiences?

I think, as a promoter, the fact that I’m an artist has made me very artist friendly. I can see things from their point of view, and I get on very well with a lot of artists. I’m always trying to make them feel at home first and I really want things to go right for them. I’m constantly looking at things from an artist’s perspective, and I think that’s been evident throughout my career.

With Vicar Street, while we’ve hosted some of the biggest artists in the world, the real success of the venue is our relationship with Irish artists. That’s what we’re most proud of. They’re the people who really keep our doors open, and we’ve forged incredibly strong relationships with them over the years.

It’s such an amazing room. Harry Crosbie built an incredible space, and Peter Aiken has run it in such a way that he’s always put a brilliant team around it. I think people really appreciate how friendly it is there and how welcome you’re made to feel. It sounds great, the acoustics are excellent, and it feels great.

Our crew are a huge part of that. Paul Aungier, who sadly passed away in 2024, was responsible for the sound for many years and always made sure the PA was world-class. His son Rory has taken over and continued that standard. The Soft Productions team do amazing work with lighting and visuals. Jake and all the lads on the door are legends, we get so many letters about how friendly and welcoming they are. There’s a bit of craic, and it really reflects the spirit of the community as well.

Comedy has also become a huge part of my job which I’m really proud of. Vicar St is an incredible room for comedy, and over the years I’ve become great friends with most of the comedians in Ireland. I think the venue has made a real difference in that field, and I’d like to think I have too.

You’ve been programming Vicar Street for over 20 years; what keeps you inspired after all this time?

I’m not always inspired but I’m very privileged to have a really wonderful job!

Yes, it can be exhausting, and my energy levels aren’t what they once were, so I can’t put in the shifts I used to. But I’ve learned how to box a bit more cleverly. There are occupational hazards, booze being the big one, so you have to mind yourself which I’m not always great at.

But the thing that really keeps me inspired is the artists and, in the case of Vicar St, the neighbourhood. That’s it. Naturally I’m not a fan of every show I put on or every artist I book, but the quality of what comes through our doors is phenomenal. And it’s really the Irish talent that inspires me most. Seeing artists come back again and again, watching their growth over time, that’s the real reward.

Over the years, is there one show at Vicar Street that really stands out to you as unforgettable?

It changes all the time, there are just far too many moments, and they’re always shifting. A recent one that really stands out for me is Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings. They’re very special artists. They first played Vicar Street back in 1999 and the recent shows were their first visit to Ireland for 14 years. It felt really special and they’re just incredible at what they do.

Then you have things like Tommy Tiernan doing almost 400 nights in Vicar Street, that’s extraordinary. And Dara O’Briain is about to do his 250th night! Being part of those kinds of journeys, working with artists of that calibre, is amazing.

I really love it when an Irish artist is doing their first night in Vicar Street. Those moments are always very special. It’s such a significant milestone in someone’s career. Revelino were a pretty big band in our time, but we would never have been able to sell out a venue the size of Vicar Street. We sold out the Tivoli once, maybe eight hundred people, that was it. So seeing artists come through, do their first night, and then come back again and again, building to hundreds of shows - that’s incredible to witness.

Of course, we’ve had superstars too like Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Paul Simon, all of that. But for me, it always comes back to Irish artists.

Damien Dempsey & Christy Moore have both just done their traditional series of nights at Xmas in Vicar Street, and those shows are just incredible every time. And I’d single out Lisa O'Neill as well - I find her utterly compelling. She’s such an extraordinary artist.

Kneecap just sold out two nights at The 3Arena last month too. I find them genuinely inspiring and I’m excited to see them at All Together Now this summer.

You’re also a musician yourself. How does performing and creating your own music influence the way you approach your work at Vicar Street?

To flip that question around a bit, I actually think my work at Vicar Street had a huge influence on my own record. Being so close to incredible talent all the time definitely seeped into me by osmosis, and it pushed me to set high standards for myself. I really wanted to make a strong record, to do a really good job.

Winter Song was probably the biggest moment for me as a songwriter. It was the first time I really felt like I had found my own natural singing voice. The whole thing was initially just a home-recording project but I had written about 10 other songs when I wrote Winter Song. My wife Karen really loved that song and started encouraging me to make an album properly. We agreed on a budget that we could afford, and I ended up spending over four times that amount! If we’d known that was going to be the budget at the start, it never would have happened. But she was completely supportive even though it meant making some financial sacrifices along the way.

But when we got the vinyl test pressings, we bought a really nice bottle of wine, sat at home, put the record on the turntable, and it sounded amazing. When Karen said, “It was so worth it”, that was the magic moment for me - just seeing how pleased she was. It was a really magical moment for both of us.

I’m genuinely so proud of the work I’ve done on it. I really am.

Your family has deep roots in The Liberties, with connections to the Iveagh Trust buildings and to Guinness. Can you share a little about that history and what it means to you today?

It means a huge amount. It’s the sense of community more than anything, that’s what the neighbourhood gave me and what it instilled in me. As I said, I lived in Ringsend from ’63 to ’68, but I spent practically every weekend in The Liberties with my aunt and my grandparents. My aunt was like a second mother to me.

She was like a living saint in The Liberties. She was always “going on a message,” as she’d say, collecting someone’s pension, paying a bill for someone, sometimes out of her own pocket. She was always doing things for people in the community. Because of that, I always felt very at home there, and I still do. I’ve always felt deeply connected to that part of the world.

So when I was offered the job in 1998, it added an enormous amount of resonance for me. The fact that Vicar Street is in The Liberties, in the area my mother was from and where I spent so much of my childhood and youth, means a great deal to me.

At the time I started there, my mother wasn’t well. She passed away eighteen years ago now, so she missed a lot of my time working there. But she loved it too. She loved that the venue was in The Liberties, and she was still with us for the first eight years of Vicar Street, which meant a lot.

I have programmed the Comedy Festival in the Iveagh Gardens since 2007 and we also run the Live at the Iveagh Gardens concert series there. That links back again to the Iveagh Trust and to Guinness, which is another layer of connection for me.

So yeah, I just have a very deep bond with the neighbourhood. It’s always been there in my life.

How has the area changed in the time you’ve known it and what do you think has stayed the same at its heart?

During lockdown, when the government was funding events to help support venues, I came up with an idea called Vision at Vicar Street. Different musicians and comedians performed, and Tommy Tiernan interviewed them.

One of those conversations was with Lisa O'Neill, and they really spoke about the energy in the neighbourhood, the sense of community, and something that exists not just in the people but in the physical environment as well. They both talked about this undercurrent of energy they feel in Vicar Street and in The Liberties more broadly.

People still really look out for each other here. That’s something that’s stayed very strong.

It’s also something the city is badly missing in general. We need to bring more people back into the city, to actually live there, to build a living city again. The area has obviously been gentrified to some extent, but there are still a lot of people who’ve lived there for generations, who are still rooted in the neighbourhood. And long may that continue, because that continuity really matters.

Those families, that sense of community, that is the heart of the place, and it’s still there.

Is there a particular place in Dublin 8 that feels especially meaningful or inspiring to you?

For me, it’s the Iveagh Buildings. That’s the place I always come back to. They’re hugely meaningful to me.

But there are other places too. Meath Street, for one. Catherine’s Bakery was a massive part of my childhood. I used to have three pink slices every Sunday in my granny’s. That's a very strong memory for me.

I love The Thomas House as well. Kevin, Gar, Sarah and the whole team there. It really feels like a proper part of the neighbourhood. It’s my favourite pub in the city. Not just because it’s across the road from Vicar Street, but because it genuinely feels rooted in The Liberties. I absolutely love it.

Some Neck Guitars has become a wonderful spot too, in fact, that’s where I’m heading off to later today.

And St Patrick’s Park as well. I love that place. When I think of it, I can still see my granddad sitting there on a Sunday morning, reading his newspaper, and I’d run over to tell him that dinner was ready. It’s a gorgeous part of the city.

How do you see Dublin 8 as part of the wider music and cultural scene in Ireland?

Well, I think Vicar Street has become one of the most iconic venues in the world, not just in Dublin. Because of that, it brings a huge number of people into the city, and specifically into Dublin 8. It draws people into the neighbourhood, which plays a really important role in the life of the area.

At the same time, I think the loss of places like the Tivoli Theatre was devastating. I think it was a disgrace, to be honest, it never should have been allowed to be knocked down. We’re losing too many cultural institutions in the city. I wrote I Love This City after a Save The Cobblestone march and The Complex is under serious threat of closure now too which is a disgrace.

Cultural institutions are under real pressure, and that’s not just a Dublin issue, it’s happening in cities all over the world at the moment. But for a country that prides itself so much on culture and the arts, I don’t think we support them nearly enough. You could even call it a bit of a pretense at times.

There are positive signs though, the Basic Income for the Arts is a genuinely great initiative and a very encouraging step but we still need far more support for the arts in Ireland. We really do.

You released your solo album In Our Hope Stars Align last January. How has that journey been for you, stepping forward as a solo artist in your own right?

It was a surprise, a very pleasant one, and a real gift. I always wished I could write songs and when I finally did crack the code on Dylan’s 80th, I was ecstatic.

I wrote the bones of about twenty songs and chose twelve for the album. It all started as home recordings. My friend Ciaran Tallon recorded four early demos on Logic for me and has been hugely supportive throughout the whole journey. I bought Logic myself and Ro McHugh and Ciaran taught me the basics. I actually bought Logic the day of a Save The Cobblestone march and went home and wrote I Love This City that night.

At the march, I met Brian Brannigan from A Lazarus Soul, who I hugely admire. Long Balconies is one of the greatest songs ever written about Dublin and the brilliant Joe Chester, who plays in his band, produced my new single I Love This City.

I had absolutely no interest in playing live at first. Then my friend Leagues O'Toole invited me to take part in a collaboration at the National Concert Hall with the Crash Ensemble as part of Musictown. That was my first ever solo show, playing twelve new arrangements of the album just two days after my 62nd birthday. It was a wonderful experience and a huge privilege.

Six weeks earlier, I’d done my first ever solo performance at Féile na Bealtaine, opening for Adrian Crowley in St James’s Church. I did twenty minutes on my own, just to check I wasn’t awful and that I could actually sing my songs live. I made myself as vulnerable as possible, and thankfully, I wasn’t dreadful!

After that, I played All Together Now with my band, The Beautiful Losers, who are great friends and amazing musicians. We’ve got a show coming up in Whelan’s very soon on Friday 16th January. I felt it was important to do the album at least once in Dublin coming up to the first anniversary of my album In Hope Our Stars Align.

Can you tell us a little bit about the album itself and some of the background stories to the songs?

I see the album as a series of love letters and protest songs. Stepping forward as a solo artist at this stage of my life has been completely unexpected, but incredibly meaningful in so many ways.

The first song I wrote was Black Satellite, which I wrote on Bob Dylan’s 80th birthday. That day I was reading Chronicles, and there are a couple of scenes in the middle of the book where he writes about New York and visiting Woody Guthrie that really struck me. My wife and I also spent our honeymoon in the Chelsea Hotel, so the song became this loose love letter to New York, to Chronicles, and to Bob himself. Black Satellite is very much a tip of the hat to Bob’s sense of humour and there are a few gags in there too.

After that, I wrote Bulletproof which is full of jokes – it’s built around the only pre-existing line that I had written before I wrote this album: “If I had Paul Newman’s eyes, Sinatra’s cool, I’d be a killer just for you.” I always loved that line and thought it was funny, so I wrote a song around it.

Then I really got stuck into writing political songs. Fire Drill and Knives were written around the same time. Fire Drill was written as the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday was approaching. I was reading a lot about it, trying to educate myself, and at the same time I was reading books by Thích Nhất Hạnh, who died just before that anniversary. His book You Are Here was on my desk, and that phrase felt perfect for the song.

In Fire Drill, I wanted to talk about the preciousness of life, in light of the British Army murdering innocent Irish people on Bloody Sunday, and to bring in the peace activism Thích Nhất Hạnh championed. I was also inspired by Seamus Heaney’s lines about “hope and history rhyme” and “hope for a great sea-change”. The album title, In Our Hope Stars Align, comes directly from Fire Drill: “Slow down, take your time, in our hope stars align.” The opening line of Fire Drill: “Taken down by the lies you live”, was also very much about the normalisation of barefaced lying, particularly from people like Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. Something has to give.

Knives came from my frustration at greenwashing, and the lack of urgency around the climate crisis. I was inspired by David Attenborough’s speech at COP26 and I always loved the line from The Untouchables: “a knife to a gunfight”, and that became a metaphor for token gestures. But again, I tried to keep hope in it: “Reach out for the high notes that blow us all away, the living saints and the lifeboats that save us every day.” That image of lifeboats came from thinking about people fleeing war, trying to find safer lives.

The rest of the album is a mix. I Love This City came after the Save The Cobblestone march. Neon Lights is a tribute to Mark Lanegan, written after his death. He lived in Kerry, struggled with addiction, and wrote incredibly powerful books. He was only a few months older than me, and his death hit me hard.

Turn On Your Radio is probably my most despairing song. It’s basically saying: wake up, cop on: “we’ve travelled miles to get here, we’re running out of road.”

Come Alive, the opening track, was written on my daughter’s 21st birthday. It was the first time we’d had friends and family in the house after the lockdown. It was a beautiful sunny day and the music was playing, and it became a love letter to family, friendship, and music itself. A proper feel-good summer song.

Hairpin Bends is probably my favourite song on the album. I wrote it after heart surgery. It’s melancholic, but it’s also about resilience and gratitude and about rediscovering music. And We Have It All, the closing track, is a love letter to my wife and kids: “We have our days when we need to recover / We have each other in a world full of colour / We have it all.”

Beautiful Losers, which a lot of people say is their favourite, came from the title of the Leonard Cohen book Beautiful Losers. I read it to Karen years ago. I had COVID on our wedding anniversary and couldn’t go out to buy her a present, so I wrote her a song instead, a love letter to her and a nod to Leonard Cohen!

So yeah, when I look at it now, the album really is a series of love letters and protest songs. And I feel like I covered a fair bit of ground in it lyrically too.

What advice would you give to younger musicians or promoters coming up in Dublin today?

Just believe in yourself, you know, trust your instinct to believe yourself.

What’s next for you, both at Vicar Street and with your own music?

Making music is part of my life for good now I hope and I’m really enjoying writing songs again. I’d love to make another record soon but I’m not sure what shape that will take or how I’ll go about it. Or how I’ll pay for it! And I do want to play live more often either with the band or solo.

In the meantime, I’ve got the show coming up in Whelan’s on the 16th of January with a really brilliant band. I’m playing guitar, along with Brendan & Ciaran Tallon from Revelino on guitars. We’ve got Gary Sullivan on drums, Gavin Fox on bass, Cormac Curran on keyboards and Yvonne Tiernan on backing vocals. There also might be some exciting announcements coming soon as well for the next Culture Date with Dublin 8 festival, so watch this space!

I’m still obviously deeply involved in the day-to-day life of Vicar Street, which continues to be a huge part of my world. So for now, it’s about keeping all of that in balance, staying curious, staying creative, and seeing where the music leads next.

Quickfire Round

First gig you ever saw at Vicar Street?

The opening night was Tom Robinson, supported by Shay Cotter.

Dream artist (living or gone) you’d love to see play there?

Elvis Presley

One word to describe The Liberties:

Community

Favourite Dublin 8 landmark or hidden gem:

The Thomas House