Dublin 8: A Postcode Like No Other by Turtle Bunbury

Essay by Turtle Bunbury for Culture Date with Dublin 8, 2019

Two, four, six, eight, who do we appreciate? Actually, it’s all about the last number next weekend (May 2019). Eight. As in Dublin 8. D8. Or DO8 as it seems doomed to become in the Postcode Future.

Now in its third year, Culture Date with Dublin 8 is a homegrown festival that takes place across a wide spread of the city over the weekend of 18-19 May (2019) when a number of prominent cultural, historical and architectural icons are opening their doors for free tours, workshops, exhibitions and talks.

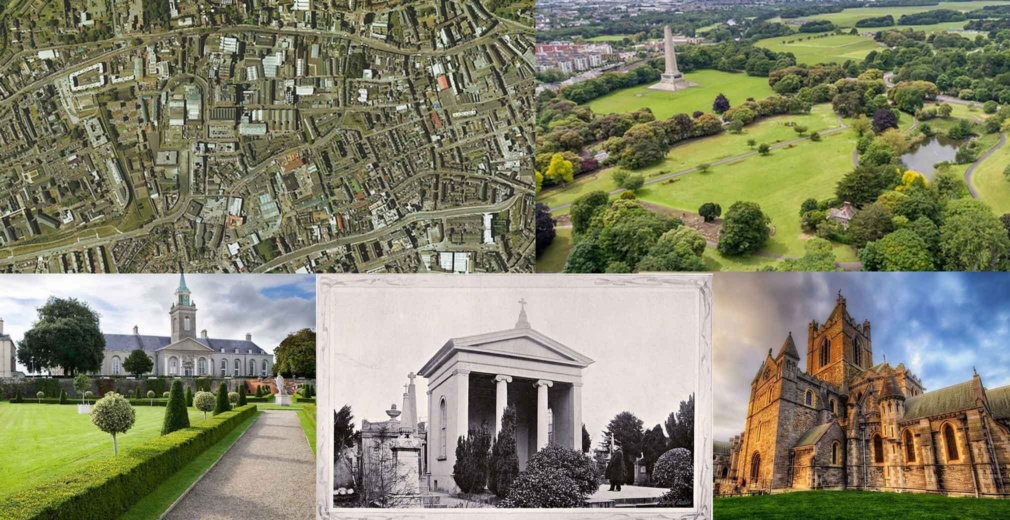

In the great game of Postal District Top Trumps, Dublin 8 has a bunch of aces up its sleeve. In part that’s because it includes Phoenix Park, the largest enclosed public park in Europe, within which you’ll find the largest obelisk in Europe (the Wellington Testimonial), the oldest cricket club in Ireland, the third oldest zoo in the world and our President’s private abode (Áras an Uachtaráin)(1). But Dublin 8 can stand proud even without that splendid 1,750 acres of landscaped parkland.

The Phoenix Park

Its principal landmarks include a brace of ancient cathedrals (Christ Church and St Patrick’s), Marsh’s Library, Richmond Barracks, Kilmainham Gaol, Dr Steevens' Hospital (and the Edward Worth Library), the Guinness Brewery, the Italian palazzo-inspired Heusten Station and the Irish National War Memorial Gardens.

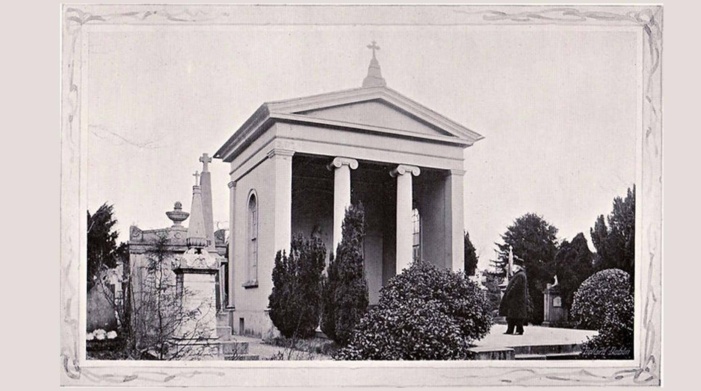

It also has Goldenbridge(2), Ireland’s first non-denominational cemetery, as well as Dublin’s oldest graveyard at Bully’s Acre(3), beside IMMA, and one of the largest Viking burial complexes in western Europe at Kilmainham-Islandbridge.

Goldenbridge Cemetery

Architectural enthusiasts will note that the Guinness Storehouse was the first multi-storey steel-framed building constructed in Ireland, while art-lovers have IMMA (Irish Museum of Modern Art), as well as the National College of Art and Design (NCAD), Ireland's oldest art institution, on Thomas Street.

As may have been inferred from the above, Dublin 8 spans the Liffey and so bucks the mythical mantra that even numbered postal districts are southside and odd ones are north.(4)

This curious glitch harks back to 1892 when a spanking new post and sorting office opened on James’s Street on the southside. The Viceroy, ensconced at the Vice-Regal Lodge (now Áras) in Phoenix Park, immediately became the new office’s most prestigious client.

Dublin 8 was born quarter of a century later when the Post Office introduced new postal districts to make life easier for the sorters and postal workers. With the city still smouldering after the Easter Rising, nobody was about to disrupt the Viceroy’s postal service so it was agreed that Phoenix Park and Islandbridge would be included within Dublin 8. In 1923, the new Free State government not only painted all the post boxes green but also formally adopted the district codes. (5)

As such, Dublin 8’s catchment area also takes in Dolphin's Barn, Inchicore, Kilmainham, Merchants Quay, Portobello, South Circular Road, the Coombe and the Liberties

Aerial View of The Liberties

The history of the area is impressive. The first glimpse of humanity is a fish-trap plucked out by archaeologists a few years ago; somebody popped it into the Liffey by Victoria Quay about 2,200 years ago.

Early Christians are hinted at from St John’s Well near IMMA but it's inevitably the Vikings who made the first significant mark. As revealed in great detail at the Dublinia museum beside Christ Church, the remains of dozens of warriors have been excavated at a major ninth century Norse Viking base (or longphort) at Islandbridge, complete with swords, spears, shields and other artefacts.

September 2019 will mark the 1100th anniversary of the Battle of Áth Cliath, fought at Islandbridge, in which the Dublin-based Vikings annihilated an Irish coalition, slaying the High King and five other kings in the process.

On the plus side, the Vikings gave us Christ Church Cathedral, to which people are invited next weekend to ring the tower bells, explore the crypt or marvel at its glorious medieval-inspired floor, made up of 84,000 tiles in 64 designs from griffins and lions to black and white chevrons and fleur-de-lis.

Christchurch Cathedral- Photo Credit Thomas Hurst

Bell devotees are also bidden to St Patrick’s Cathedral, a legacy of the Norman age, where, as well as a tour of the bell-tower, they can behold the incredible tomb of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, an Englishman who allegedly arrived in Ireland with sixpence in his pocket and fetched up as the richest man in the land. Also here is the grave of the cathedral’s most famous Dean, Jonathan Swift, of ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ fame.

It was Swift’s handsome nemesis Narcissus Marsh, Archbishop of Dublin, who founded Marsh’s Library beside St Patrick’s. As part of Culture Date (May 2019), this fabulously atmospheric library is inviting children to participate in a free LEGO Treasure Hunt to track down mini-figures of historical writers, while inhaling the wistful aroma of 25,000 rare books, the youngest of which was printed in 1745.

From the Normans until the Tudor Age, much of present-day Dublin 8 was an extensive sheep farm. In 1662, the Great Duke of Ormonde stuck a wall around a large chunk of it, filled it with deer and pheasants and rechristened it Phoenix Park. (6) The land between Phoenix Park and Kilmainham had previously belonged to the Knights Hospitaller. In 1680, the Great Duke established a retreat for war veterans on the site of the knight’s priory at Kilmainham. Known as the Royal Hospital, this evolved into the Irish Museum of Modern Art, where next weekend’s (May 2019) visitors can avail of free tickets to catch the final weekend of ‘Gaze,’ an exhibition dedicated to the eminent 20th century artist Lucian Freud.

IMMA- Irish Museum of Modern Art Formal Gardens

The religious upheavals of the 17th and 18th centuries ignited a boom in the Liberties and the Coombe where the manufacture of silk and wool drew thousands of weavers of Irish, English, Dutch and French Huguenot origin. Many of the latter also excelled as jewellers, silversmiths and bankers.

Modernity gradually inched its way into Dublin 8 with the coming of canals, railways and trams, as well as distilleries, breweries, factories and engineering works at places such as St James’s Gate and Inchicore.

Next weekend (May 2019), visitors are welcome to Richmond Barracks in Inchicore for tours, as well as a workshop in local Biodiversity. Established for the British Army in 1810, the barracks came to prominence during the Easter Rising when over 3,000 suspected rebels were held here. Among them were six of the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Republic; all seven were subsequently executed at Kilmainham Gaol, which will also be providing free tours over the weekend, as well as presenting new, and previously unseen Civil War artefacts.

Today, Dublin 8’s streets, alleys and quaysides are replete with hipster cafés, cocktail bars and family-friendly restaurants. Among other highlights next weekend’s wanderers might consider are an outdoor concert in the temple at Goldenbridge Cemetery (founded by Daniel O’Connell in 1829), story-telling and theatrical re-enactments on World War One at the National War Memorial Gardens and various walking tours laid on for historical and photographic enthusiasts.

1. Phoenix Park is also home to the Chief Secretary’s Residence (now the residence of the U.S. Ambassador to Ireland), Ashtown Castle (a medieval tower house that became the Under-Secretary’s Residence, subsequently the Papal Nunciature and now the Phoenix Park Visitor Centre), the Magazine Fort. Farmleigh House appears to be in Dublin 15.

2. Goldenbridge Cemetery, which was founded by Daniel O’Connell in 1829 (and predates Glasnevin by three years) is the first non-denominational and garden cemetery in Ireland.

3. Bully’s Acre (3.7 acres, officially the Hospital Fields) beside IMMA is said to hold the graves of men slain at the Battle of Clontarf, including Brian Boru’s son and grandson. It later became a pauper’s graveyards and holds tens of thousands of bodies although grave-robbers snatched untold numbers of corpses to exchange for surgeon’s shillings in the Georgian Age; such bodies made ideal dissection material for anatomy students. When the rebel Robert Emmet was executed on Thomas Street (a D8 highway) in 1803, he was initially buried at Bully’s Acre but his body was later removed and has vanished. So too was the body of the Kildare champion boxer Dan Donnelly; his arm was hacked off by medical students and hung in The Hideout Pub in Kilcullen for many years. St John’s Well by Bully’s Acre was a popular gathering point until such crowds were banned in 1755. Bully’s Acre was closed to the public following the cholera epidemic of 1832, though some burials took place until 1835.

4. The other postal district to span the Liffey and take in some of the northside is Dublin 20, which includes Chapelizod. If you’re a bird, the tallest things to watch out for are the Wellington Monument (a 62 metres (203 ft) tall obelisk commemorating the victories of the Duke of Wellington), the Guinness Storehouse, the Papal Cross (35 metres, 116 feet) and the belfries of the two cathedrals. That said, there’s stiff competition ahoy for the “tallest of all” as foundations are laid for Harry Crosbie’s new eight-storey hotel on Vicar Street. It also has a bunch of fine bridges of Islandbridge, plus Essex Quay and Wood Quay.

5. For all that, Dubliners themselves didn’t really start using the numbers until 1961 and now, nearly sixty years later, those numbers are in steady decline as, wearily beaten into submission, we the people turn to postcodes.

6. The park was opened to the good people of Dublin by the Earl of Chesterfield, who also initiated a major landscaping and plantation programme in 1745. Subsequently landscaped, the OPW-run park recently won the coveted position as Ireland’s Favourite Local Attraction in the Irish Independent 2019 Reader Travel Awards.