Urban Myths and Legends by Mark Jenkins

In a world increasingly permeated by fake news, in this post we look at a few myths, urban myths and legends associated with the area.

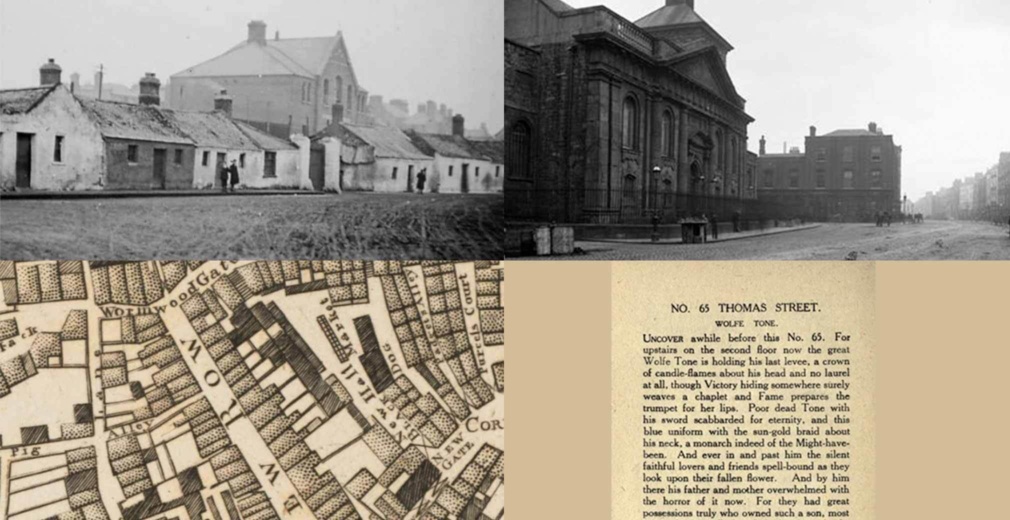

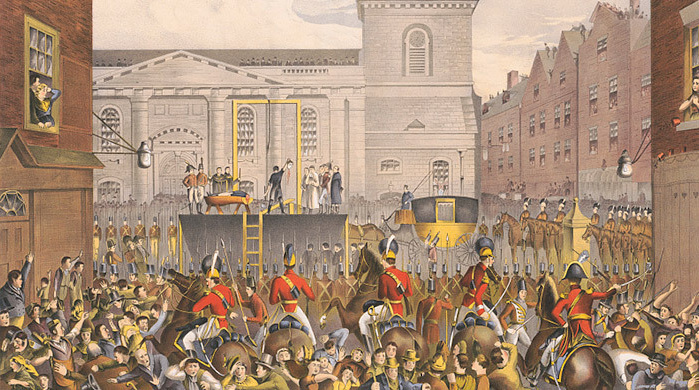

Although never living in Dublin 8, one of the most prominent figures associated with the area is Robert Emmet, who faced his gruesome fate on Thomas Street on the afternoon of September 20th 1803. His speech in the dock of Green Street courthouse remains one of the most affecting, eloquent and definitive speeches in Irish history. There is a lot to detail and absorb about the life, death and legacy of one that was so young, but one common theme crops up. This generally happens when photos are uploaded of St. Catherine’s Thomas Street or the vicinity of the temporary scaffold erected in the roadway in front of the church.

When posted on social media platforms the comments usually include words along the lines of “that’s where Robert Emmet was hung, drawn and quartered”. The words are also included in many relatively modern day publications and newspapers when referring to his death.

For many growing up in the Dublin 8 and wider city area the tale of the bold Emmet would include those words, though it is just slightly off the gory but no less gruesome truth. He was indeed condemned to be hanged, drawn and quartered, the general sentence for high treason. Most of these sentences were issued by Lord Norbury (John Toler), the notorious Chief Justice of the Irish Common Pleas, and his callous arrogance and perceived lack of humanity led to him being nicknamed “The Hanging Judge”. He famously even fell asleep during a trial such was his dis-concern at the fate of those facing him. The fact that the gruesome elements were not carried out in full were due to the unprepared nature of the executioner Tom Galvin to carry out the act. It was a stern statement and warning by authorities to the public by holding the execution in such a prominent part of the city and indeed where the scene of the failed Emmet rebellion took place. A temporary gallows was erected in front of St. Catherine’s in the roadway. Robert Emmet uttered his final words, “My friends, I die in peace with sentiments of universal love and kindness towards all men” and after being hanged for half an hour, Galvin awkwardly beheaded Emmet on a butchers block and proclaimed “This is the head of a traitor, Robert Emmet” whilst holding the head aloft.

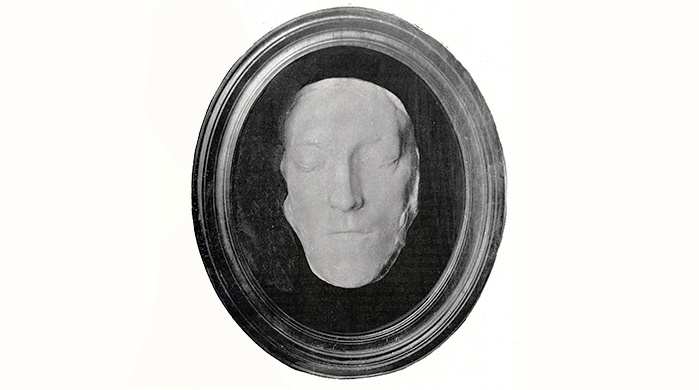

One other element many may recall being told as a kid and many have related to me, was that Robert Emmet’s head was rolled down Bridgefoot Street. Such a distinct image was imprinted on many a childs’ memory when told this. The key to debunking this myth is attached to two factors. Firstly there is no documentary evidence or contemporary recollections that mentions his head being rolled down what was then called “Dirty Lane”. The second fact is that death masks were made of Emmet. This would not have been possible if in the immediate aftermath his head was rolled down such a steep incline.

65 Thomas Street

One suggestion put forward but again proves untrue was one alluding to the possibility of the premises of the public house hosting the wake of Wolfe Tone. The pub, now named Tom Kennedy’s and still referred to as O’Neill’s by many locals, has a long history of links to rebellion. Indeed in the months subsequent to the 1798 rebellion among the list of those rounded up and arrested by Dublin Castle authorities we find the tape weaver Thomas Ellis who lived at the address. Many of those entrenched in the plotting, planning and participation of the rebellion in Dublin were from the Dublin 8 area and often involved in different aspects of weaving and associated trades. 65 Thomas Street would go on to be a supposed secret meeting spot for many of the major figures in the fenian movement in the mid 19th century.

Several of the workers that were building John’s Lane were having meetings locally and were inducted into the movement by more senior figures. Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa would travel up to Dublin to Kingsbridge station (Heuston) to meet with other Fenian leaders and members in Tom Kennedy’s, then known as Bergin’s public house. Unfortunately for him he was being spied upon and information about these supposed secret meetings were filtering back to Dublin Castle. The subsequent arrest of a host of leaders and the information collated led to their sentencing, detainment and dispersal etc.

This in turn delayed the building of John’s Lane church (the church of St. Augustine and St. John the Baptist) and it became known colloquially as “The Fenian Church”.

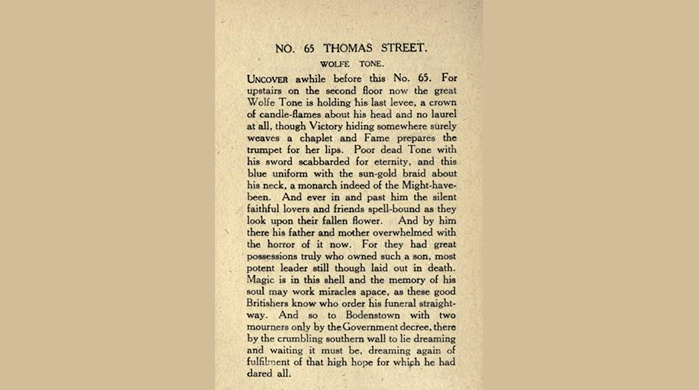

With all these associations over different revolutionary periods it is not such a far misplaced suggestion that the wake of Tone was held there but his associations lied firmly just up the road at High Street. The buildings on High Street are long gone so that may have prompted the theory as put forward by Daniel Lawrence Kelleher in his 1920 book “The Glamour of Dublin”, depicting the scene above the public house with the remains of Theobold Wolfe Tone before removal to his final resting place in Bodenstown. Although the former house number on High Street is debatable number sixty five is suggested in several sources, but he certainly had family and friends living on the street.

Blackpitts

Something we hear on occasion is a myth in relation to the origin of the name of the Blackpitts area of Dublin. The region in the Liberties and surrounding district has for centuries been associated with the weaving, textile, leather trade and related industries. Subsequent to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 many Huguenot families fled religious persecution and settled in the area, bringing with them new skills and approaches to production in these trades. Coupled with that was also a seventeenth century statute that encouraged "the protestant stranger" to settle in Ireland. In a previous post we alluded to the relatively recent and extensive excavation of numerous tanning pits, uncovered preceding the development of the area. The myth which is sometimes mentioned was the possibility that the name Blackpitts derived from mass graves in the vicinity that were from the days of the Black Death. The disease caused thousands of deaths and overall circa fourteen thousand in Ireland in the 14th century. It was said that there weren’t enough coffins to facilitate individual burials due to the rate at which the disease took hold and many were buried in mass graves. This may seem a natural link to the placename but again there is no archaeological evidence or historical reference to there being any form of black death mass graves in the Blackpitts area. The tanning vats used to dye textiles and leather that lend their name were there for many generations across centuries.

The Green Lady

One legend of Cook Street leads us to the surviving city gate of Dublin at St. Audoen’s church. Locals for generations have passed on reports of seeing an apparition of “The Green Lady” at the steps leading from the gate to the church itself. In times past there was a foundling door inside the city gate at the church. Poor people who could not provide for a newborn child, would place the baby into a basket at the door which would revolve, hoping that the church could provide a better chance in life for the child. It is believed that the ghost of the green lady is returning to find her child, and many people that grew up or went to school in the area recount living in fear of seeing this apparition.

The Dolocher

In the seventeenth century the main western gateway into Dublin must have looked a daunting site. As you neared the city walls at Cornmarket you were met with the four towers of Newgate prison, and also in the proximity was a debtor’s prison known as the Black Dog. It is possible that the name was taken from a local inn which had as it’s sign an image of a dog. The Talbot Inn was one popular local in the area. One man sentenced to death and detained in the prison was of the name Olocher. When his cell was opened on the planned morning of his execution they found he had taken his own life. The following night a sentry on duty at the city gate we mentioned previously at St. Audoen’s Gate was found lying senseless at this post. On composing himself he said that he had been rendered paralysed by the apparition of what he described as a black pig. In the nights after this the same reports from several guards told of the same form appearing, and from then word spread that the black pig was causing terror about the city. A guard at the Black Dog prison disappeared from his post and people made the presumption that he had been devoured, and that Olocher had returned in the form of a black pig. Numerous attacks on women were reported and a resolution was sought. A band of people decided if they killed every pig in the city and surrounding areas they would be sure to be rid of the beast. After a night of seeking out every pig that roamed the city (they were allowed freely roam the streets as they would eat a lot of the discarded food remains that would become rubbish) the next morning there was not a single carcass to be found. There would be no sight of The Dolocher (now named so by one of the women who saw the black pig) until the next year. Tales of sightings returned but one attack on a blacksmith resulted in his apprehension. On his capture it was found that cloaked in a black pigskin was the very man that had supposedly disappeared from his post at The Black Dog! He had helped Olocher commit suicide and when the reports of the pig spread he had joined the group of people to slaughter them but had robbed and stored them for personal gain!

I hope you enjoyed this exploration of a few of the urban myths and legends of Dublin 8. Please do share any recollections or comments on the social media pages for Culture Date with Dublin 8:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CultureDatewithDublin8

Instagram: https://www.facebook.com/CultureDatewithDublin8

Twitter: https://twitter.com/culturedated8

Photos in this post other than those by Mark Jenkins are public domain.